Contents

- An Overlooked Ingredient for Startup Success

- Why Take Time to Get Organized?

- The Larger Strategy for Success

- FuSca Light for Startups

- Overcoming Objections

- Getting Started

An Overlooked Ingredient for Startup Success

A mid-sized startup near Seattle years ago was the fifth a group manager I knew had worked in. Of the other four, only one survived. That one had stopped work for two months to get its processes in order! His current employer was a disorganized mess, with no departmental budgets and minimal project management. Eventually it went through three rounds of layoffs and was acquired for a fraction of the original investment.[1]

Years later, an entrepreneur told a professional group his classic startup story, beginning as a one-person side operation and building the business with insane work hours. When the company had 30 people, it struggled for a three-year period to get beyond a plateau around $2 million in sales, meanwhile putting the founder’s marriage and personal finances at risk. He said he finally realized the problem was him—he had to let go of control. He hired a life coach to help him do that, and then a chief operating officer to get things organized. The next year the firm finally moved past $3 million in sales, and a few years later sold for $7 million.[2]

These anecdotes hint at the need for startups to invest time in organizational structures and processes (“organizational development”) earlier than they usually do. Research into high-performance teams makes clear process formalization improves team-level performance,[3] and all startups are small teams in the early stages. Without wading into the debate about how much formalization helps rather than hurts, some definitely helps. For an entrepreneur hoping to avoid the problems in those stories above, the question becomes how much to do at each point in your company’s development. At the time of this writing[4] there has been virtually no scientific research into why and when startups should put formal business processes and structures in place. But there are many hints worth considering, detailed in the next section.

This page explains why to take time to implement some structure and process in a startup of four to 12 people. You can either create your own custom approach together, or the page also walks you through adopting a light version of the work-management process called “Scrum.” In this stage, the evidence suggests other priorities are more important to survival than organizational development, but OD should not be completely overlooked. My approach, called “FuSca™ Light,” helps startups avoid some of the time-wasters that tend to plague new companies stuck in a “just-get-it-done” mentality. However, it leaves out many of the details of full Scrum or Kanban until having more people introduces far more potential inefficiencies and conflicts. Though reading other parts of this Full Scale agile™ (FuSca) site will provide useful context, this page and the steps linked at the bottom are intended to be sufficient for a startup to implement FuSca Light. Some of the information repeats content elsewhere on the site, with links to the related sections.

If you’re already convinced it is time for your startup to get organized, you can skip to “The Larger Strategy for Success.” Otherwise, if you are an entrepreneur who has at least three co-workers and has found this page, keep reading to understand why that’s probably proof it is time!

Why Take Time to Get Organized?

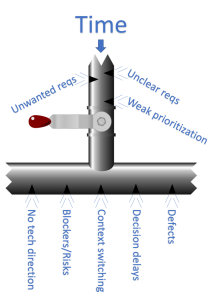

There are a number of ways small startups waste time without realizing it, regardless of what kind of work they do. This is just a partial list:

- Too much or too little upfront design and architecture work.

- Stopping to understand what is required after work has already started.

- Poor line-of-sight between actual customer needs and the team, so the team creates unneeded deliverables or does significant rework.

- Conflicts among members about technical direction or who is doing what, especially about a deliverable already under way.

- Failure to identify preventable dependencies and other risks before they block progress.

- Failure to identify all work required for a release (especially nontechnical needs) until nearing a release date.

- Finding defects late in the release cycle, and thus holding up the release.

- Releasing defects that could have been prevented far more cheaply, and which hurt the company’s reputation with customers.

- Frequent context-switching due to uncontrolled priority changes.

- Team downtime while awaiting customer or founder decisions.

The most effective antidote to these problems is some degree of pre-planning of the work with customers or their representatives, plus processes to smooth coordination among workers. The Agile Manifesto attempts to strike a balance between too much and too little of these. Don’t be misled by the Manifesto’s focus on software—Agile methods can and have been applied to other types of projects, including hardware design and manufacturing.

That problem list may be why many studies indicate that the founder’s previous experience as a manager, in prior startups, and in the startup’s industry are linked to the likelihood of a startup surviving and growing. (How to define startup “success” is debated, but two common themes in entrepreneurship studies are survival past three years and growth in the number of employees.) Getting help from outside professionals, not just friends and family,[5] was helpful as well. A meta-analysis of 40 studies on startups in lower-income countries found that technical assistance had an impact on success.[6] More specifically, it concluded that training programs “should contribute… to firm productivity (for example, through the adoption of more efficient management practices).”

Drawing from a longitudinal study (the kind that best indicates causality) of 2,000 startups in the Netherlands, researchers concluded three factors involving organizational expertise were critical to surviving three years[7]:

- “The importance of work experience. Especially the young, inexperienced potential starters ought to be advised to obtain some work experience before they take the step of setting up their own firms, preferably in a paid job.”

- “The importance of a business partner… preferably an experienced entrepreneur who actively guides the new entrepreneur and may also help to solve the (growth) problems in the first years.”

- “The importance of a thorough preparation,” defined not only as having a well-developed business plan, but also “market orientation” and taking and following the guidance of courses on entrepreneurship.

After reviewing studies available by 1987, two management professors gave advice scientists still echo: “Effective action also requires a detailed knowledge both of the startup process and of the key success factors of the industry to be entered…”[8] A survey of 79 Serbian startups found that among the top six success factors were three touching on organization and process[9]:

- “Ability to manage personnel.”

- “Good management skills.”

- “Maintenance of accurate records.”

More examples come from a systematic literature review of 74 studies published after 2003 in highly regarded journals. Of 21 success factors the authors found, six seem indirectly related to processes and the education and experience of the leader or team, such as “business capabilities” and, “Experience in management of the entrepreneur.”[10] The researcher commented, “The lack of experience in management is often the main reason for the failure of new ventures. The entrepreneurs of startups rely on their previous experience and… don’t want nor try to expand their knowledge in order to achieve a bigger business range.”

A dissertation[11] found that “positive organizational behaviors affected the firm’s overall performance, employee productivity, and employee commitment,” based on survey responses from top leaders of 328 successful startups, using sales growth as an indicator of performance. Almost all of the 11 skills most of these leaders called “very important” related to internal processes: “developing a vision for the future, improving quality, team building, strategic planning, leadership development… managing innovation (and) implementing business plans, employee selection, effective delegation, managing change, and problem solving.”

Writing a detailed business plan improves the odds of success.[12] Solid evidence comes from a long-term study that sampled the business plans of 585 German companies and compared their content to survival rates.[13] The scientists concluded, “Initial planning is an important requirement of success, but cannot lift it until certain minimum constraints are met.” Those constraints include issues like sales and funding.

Nine of the 12 “how-to” entrepreneurship books at one research university library discussed structure and process decisions, many of them extensively. For example, 35 of the 50 Steps To Business Success[14] relate to strategic planning, leadership, and operations. Two are, “Identify Business Processes to Be Improved,” and, “Appoint a Leader of Business Improvement.” Section titles in Mastering Entrepreneurship[15] include, “Building and maintaining the entrepreneurial team—a critical competence for venture growth,” and, “Distilling a strong team spirit.”

The book Entrepreneurship[16] doesn’t get to “Developing Internal Processes” until Chapter 8, but it points out there is a “Malcom Baldridge Award for small firms that show exceptional skills at operational performance.” The authors make a compelling argument for focusing on operations simply in the way they define it: “Operations are the internal processes that create the value… (which) distinguishes the firm from competitors, and it is the kind of value customers are prepared to pay for.”

Logic says these issues become more important the more people you have. A textbook reporting on a 1993 study confirmed this. In the startup phase, only 16 percent of the problems were process problems, specifically “internal financial management problems.”[17] By the growth stage 58% of problems related to processes, with a higher degree of financial management issues joined by “human resource management,” “general management problems,” and issues with “organizational structure/design.”

The Larger Strategy for Success

Thus the research consensus is that a founder’s experience or training, a detailed business plan, sales growth, and funding are more critical to initial success than organizational development. But getting organized appears to be important earlier than most startups get to it. Based on the evidence above, an overall strategy for maximizing a startup’s chances of survival and growth is to:

- Do some market research before you invest a lot of time or money, to learn whether people will actually pay for your great idea (referred to as “customer discovery”).

- Especially if you don’t have much business and startup experience, attend some free Small Business and Technology Development Center (SBTDC) and SCORE classes, if not more formal business training.

- Earlier than you want to, create a detailed business plan even if you don’t intend to seek funding, and run it past SBTDC/SCORE mentors.

Note: Specific details vary by industry, so consult mentors and industry peers first. Also, the plan should be considered a living document that changes with your business. - Next emphasize developing the initial product, sales and marketing, in a series of small experiments that let you test your assumptions and change direction if the results suggest doing so.

- When you have 4 to 8 people, implement a light work management process to start gaining some of the benefits without going through all of the steps.

- Once you have 12 to 15 people, that is the time to restructure into multiple teams and implement formal work processes like Full Scale agile, with a lot of input from workers on specifics.

These steps can overlap. Certainly 1 and 2 can be done at the same time, and 3 and 4 should feed each other: That is, create a draft business plan, test its assumptions, update the plan, and so on.

Also, you do not need a formal, off-the-shelf process at either Step 5 or 6. See the “Self-Directed agile” chapter for a research-backed approach to charting your own path. If, however, you have exposure to an Agile method like “Scrum” and like it, but think your team doesn’t need the full package yet, keep reading.

FuSca Light for Startups

My preference, based on decades of research and coaching practice, is for your team to create its own structure and processes using the Self-Directed agile section of this site. That time-tested approach maximizes both your members’ empowerment, which provides massive benefits for your company’s success, and your flexibility to meet the rapid changes you face.

If the team prefers to use a standard framework, this page, and its related step-by-step instructions linked at the bottom, provide the minimum information you need to implement a light version of Scrum per Step 5 above. Generally a small startup team can get away with merely:

- Writing down the work that needs to be done over the short term, in a prioritized list;

- Formally meeting every two weeks for basic planning; and

- Gathering briefly every day to maintain the group’s focus.

When following the steps linked below, you first will designate two roles. A company founder becomes the Team Guide (or “Product Owner”), the person who represents the customer(s) and makes the final call on the order of work. (If you have multiple founders who are equal partners, they will need to decide if one person takes this role, or if they will try sharing or rotating the role.) Then ask a volunteer who is not a founder to serve as the Facilitator—the person who runs the meetings. Using someone other than a founder in this role increases the likelihood of other members contributing their opinions more freely, gaining your company the value of multiple perspectives and employee empowerment.

Next, you will choose a means for tracking the work. There are several free or low-cost options:

- The free “FuSca Light Tracker” spreadsheet—after downloading, see the “Legend” tab for instructions.

- A paper tracker posted on a wall, but only including the information shown below on the requirements (not everything in the linked section).

- Any of a number of Agile trackers that are free or cheap online.

Note: Some full-featured products offer a small number of free licenses.

Having selected the tracker, the next step is to create a “Product Backlog.” This is simply a list of most of the work you need done in the next couple of months, broken down into small-enough pieces to fully complete within two weeks, a period called a “sprint.” (Sprints can be as short as a week or as long as a month, so long as they stay the same length, but I recommend you start with two weeks until you learn the routine.) In many Agile systems those pieces are called “user stories,” which include who the requirement is for; what the specific requirement is; and why the person or team wants it. Most of those systems, including regular FuSca, add more information, but FuSca Light stops there.

“Fully complete” means designed, developed, tested, and proven to work as designed. There are psychological reasons for delivering complete small chunks at a predictable clip (see “High Predictability“), and this is a fundamental principle of most Agile methods. Simply put, the team will accomplish more per working hour at higher quality, and in turn gain a tangible sense of accomplishment. However, those chunks may not yet be useful deliverables, depending on your product or service. If you are creating a hardware product, it may simply be a proposed design of a tiny part of the final blueprint, “complete” in the sense that its creators think it would work in the larger blueprint without modification. For a marketing team, the chunk may only be the proposed “unique selling proposition,” ready for wider input and iteration before its use in external communications. In both cases, far more requirements must be finished before the entire deliverable is ready to use, but the chunk could be used now.

A startup’s backlog can and should include pretty much any kind of work the team needs to do (see “Gather Requirements”):

- Features of your product or service (“customer/user” and future “market requirements”).

- Parts of design or architecture documents (more important for hardware or manufacturing teams).

- Technical requirements needed to support multiple features or to improve your work processes.

- Defects.

- Other things you need to do for the business, like creating a venture capital presentation or hiring a new member.

Obviously you don’t list every little act. A good rule of thumb is to track the work that takes up 80% of the team’s time, which under the Pareto Rule[18] is only around 20% of all actions. Have people create “action items” to address smaller issues.

Regardless of which tracker you choose, these stories will be rank-ordered (1, 2, 3, etc.) rather than put into priority categories like “High/Medium/Low.” This avoids the lie there can be more than one “top priority.” That lie causes companies to lose focus on finishing work and to waste labor hours by spreading resources too thin. Rank-ordering doesn’t mean people can only work on Priority #1 during a sprint. However the team should only work on 1, 2, or 3, for example, not six different priorities scattered about the Top 20. And if there is any kind of resource conflict between two requirements, the higher-ranked one automatically wins.

At some point you may add “risks” to the stories, meaning issues that could prevent the story from getting done within one sprint, or possible bad results the story may cause. These may or may not become “blockers,” reasons not to put the story into a sprint (or keep working on it), because the story cannot be completed until they are addressed. Larger risks and blockers often generate their own stories or action items.

FuSca Light only has two formal meetings. One does the most critical parts of three standard Scrum “ceremonies” in a single meeting every other week. In that meeting the team members:

- Show off what they completed since the last meeting (like the Demonstration Ceremony in Scrum).

- Review and decide together who will complete what work by the next meeting (like Grooming Sessions and the Sprint Planning Ceremony).

Note: To increase predictability, you will only take on enough stories to cover 80% of everyone’s time at most, possibly less if you already have customers requiring support. - Discuss what is going well and what isn’t in the company (like the Retrospective Ceremony).

Plan on that meeting taking an entire morning or afternoon at first, though you’ll get faster as the steps become habits. If people gripe, remind them of examples your company has experienced of the time wasters listed at the start of the previous section. Those problems almost always cause unplanned meetings this meeting will prevent.

The other ceremony is the Daily Standup, a 15-minute (only) check-in with each other relative to the sprint tasks. Besides identifying problems before they become full-on blockers, these “scrums” build your company members’ commitment to each other and to your customers. That’s because each person tells the others what they plan to work on one day—and the next day have to say whether they did that or not!

To summarize, here are the two FuSca Light ceremonies:

Overcoming Objections

If you’re the entrepreneur and have gotten this far, congratulations! The sad fact is, the people in startups who seem to object most to getting organized are the founders. First off, many times these folks became entrepreneurs to escape the spirit-busting ennui created by overly restrictive procedures, endless meetings that accomplish nothing, having to meet plans instead of pleasing customers… I could go on. Of course, startup members who are refugees from big corporations will have the same perspective.

However, it is important not to “throw the baby out with the bath water,” to quote an old German saying. As the evidence detailed in the “Why…” section above proves, some degree of process discipline is necessary to get the most productivity out of a group without excess stress. And you have a grand opportunity to create from scratch a company that strikes a healthy balance between self-discipline and overpowering bureaucracy, using Agile management. Even the full FuSca process only takes about 10% of overall working time, saving much more time from getting wasted.

Another difficulty is that entrepreneurs often are scared to let go of their baby, which is understandable. First I will refer you to the second story at the top of this page. Second I will point out that if your company is successful, someday you will have no choice! One person simply cannot micromanage 20 others, much less 200, so at some point you will have to give up trying. The sooner you do, the sooner you will harness the power of multiple perspectives (“crowdsourcing”) within your own team, and free (or force) yourself to focus on building the business instead of its products.

For other possible concerns, see “Objections to Agile…” on the FuSca “Questions and Answers” page.

Getting Started

A key difference between FuSca and other Agile-at-scale methods is the detailed step-by-step instructions included for free, in the manner of a technical manual. These lead you through the process, but will not help unless you actually do them. The only way you will gain the benefits of getting organized is to do the work of getting organized! The quickest route is to decide as a team that you are going to give FuSca Light an honest, all-in try for several months, even if you are skeptical. That’s the only way to see the benefits, and seeing the benefits is the best way to overcome your skepticism. After it helps you grow past 12 or so people, you will find it much easier to adopt or create other disciplined practices important for multi-team companies and thus gain their additional benefits.

Once you have everyone’s commitment to give this a real shot, review the short explanation of the site’s Step Sets, then click the link below and get started!

⇒ Steps: “Agile for Entrepreneurs“

↑ Agile Management | ← Customize through Experimentation | → Questions & Answers

[1] I was a group manager in the same company at the time.

[2] Jeff Cope, “The Journey-Lessons from a Founder” (July 31, 2019), https://ncpmi.org/component/eventbooking/membership/the-journey-lessons-from-a-founder.

[3] See my Web book, The Truth about Teambuilding.

[4] Summer 2019.

[5] Alicia Mas-Tur et al., “What to Avoid to Succeed as an Entrepreneur,” Journal of Business Research 68, no. 11 (November 2015): 2279–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.011.

[6] C. Piza, “The Impacts of Business Support Services for Small and Medium Enterprises on Firm Performance in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review” (The Campbell Collaboration, January 4, 2016), https://campbellcollaboration.org/library/business-support-services-for-sme-low-and-middle-income-countries.

[7] Veronique Schutjens and Egbert Wever, “Determinants of New Firm Success,” Papers in Regional Science 79 (2000): 135.

[8] Charles W. Hofer and William R. Sandberg, “Improving New Venture Performance: Some Guidelines for Success,” American Journal of Small Business 12, no. 1 (July 1987): 11–26, https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878701200101.

[9] Ivan Stefanovic, Sloboda Prokic, and Ljubodrag Rankovic, “Motivational and Success Factors of Entrepreneurs: The Evidence from a Developing Country,” Zb. Rad. Ekon. Fak. Rij. 28 (2010): 20.

[10] José Santisteban and David Mauricio, “Systematic Literature Review of Critical Success Factors of Information Technology Startups” Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 23, no. 2 (2017): 24.

[11] Randel S. Carlock, The Need for Organization Development in Successful Entrepreneurial Firms (New York: Garland, 1994).

[12] Schutjens and Wever, “Determinants of New Firm Success”; Christian Serarols Tarres, Antonio Padilla Melendez, and Ana Rosa Del Aguila Obra, “The Influence of Entrepreneur Characteristics on the Success of Pure Dot.Com Firms,” International Journal of Technology Management 33, no. 4 (2006): 373, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2006.009250.

[13] R. Schulte, “Pre-Startup Planning Sophistication and Its Impact on New Venture Performance in Germany,” 295 (ICSB World Conference 2007, International Conference for Small Business, 2007), 21.

[14] Peter M. Cleveland, 50 Steps to Business Success Entrepreneurial Leadership in Manageable Bites (Toronto: ECW Press, 2009), http://site.ebrary.com/id/10173250.

[15] Sue Birley and Daniel F. Muzyka, Mastering Entrepreneurship (Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2000).

[16] Alan L. Carsrud and Malin E. Brännback, Entrepreneurship, Greenwood Guides to Business and Economics (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2007).

[17] Donald F. Kuratko and Richard M. Hodgetts, Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Approach (Fort Worth: Dryden Press, 1998).

[18] Named for economist Vilfredo Pareto by management consultant Joseph Juran, who came up with the concept based on an observation by Pareto about the distribution of wealth in the early 1900s. The ratios have held up as roughly true in a range of scenarios, such as 80% of product quality problems coming from around 20% of the causes.